CELESTIAL DETECTOR: WEIGHING LIVES FROM BELOW

2025 Collaboration with Geoff Manaugh | Text by Geoff, Images by John Becker

Written for the Lisbon Architecture Triennale/e-flux

When he came to our door, I thought he had dementia. An old man in tennis shoes and a disheveled suit, he said his car had broken down. Looking over his shoulder, I didn’t see a car. Besides, our town was in the middle of nowhere, in a remote part of Central California, hours from even a modestly-sized city. Why on Earth would he have driven here?

After the man asked if he could use our landline, saying his cellphone had died, he looked past me, as if studying our living room, and seemed to lose his train of thought. Then he turned back to me and said, “Everything’s in exactly the same place. That table’s been there for more than twenty years.”

***

At every moment, high-energy rays moving through space at nearly the speed of light collide with matter high in the Earth’s atmosphere. These collisions produce further particles, one of which is known as a muon. Muons stream down through the sky, not only reaching the Earth’s surface but penetrating it, often to depths of more than a mile, before their energy dissipates.

Muons are constantly passing through all of us—through our skin and bones, our cars and buildings, through the mountains and landforms around us. They are so small, moving so quickly, that they have little interaction with matter. We never feel them, though they are inside our muscle and bone; we never see them, though they pass through our pupils and optic nerves.

Although muons are everywhere, they are surprisingly few in number: every second, fewer than ten muons pass through an area the size of your palm, literally just a handful. With the right instrumentation, however, the passage of muons can be recorded, like light on a digital sensor, which means that, given enough time, muons can be used to create images. Similar to an X-ray, the resulting “muographs,” as they are known, reveal otherwise inaccessible voids inside even the densest of materials.

Muons offer a way to understand the world by studying what has passed through it.

***

Walking up beside me that day, my dad clearly recognized the man—although, I’d later learn, he had never set foot in our house. How the man knew about our family’s furniture arrangements would only emerge in the years to come.

My dad, an electrician less than a year into retirement when the knock on our door came, explained that he and the stranger had met nearly two decades earlier as part of a complicated job, installing new wiring, shielded ductwork, and a massively upgraded switching panel inside a small government building on the edge of town. They had not been friends but had interacted, saying hello on the street, speaking briefly on the odd electrical call-out, and nothing more.

The man’s name was Wendell Brandt. He was a physicist. Born and raised in Germany, which explained his slight but unplaceable accent, Brandt had lived in our town for nearly fifteen years. He had made an eccentric presence, always alone, whether seen at the supermarket or local restaurants, moving away altogether before I was old enough to remember seeing him.

Or had he? “You been in town this whole time?” my dad asked. He sounded cautious.

“No, no,” Brandt replied. “I came back to see things again. I’m sick.”

***

As early as the 1950s, Eric George, a British physicist working in Australia at the time, had used muography as a technique for measuring layers of rock and ice above a mine southwest of Canberra. But the field saw its first most notable success a decade later, in 1968, when Luis Alvarez, a professor of physics at UC Berkeley, brought a team of researchers to Egypt. There, they installed a muon detector inside a small room beneath the pyramid of Khafre.

Alvarez’s hunch was that, if the team could measure the number and velocity of muons passing through the pyramid above, and if he and his researchers could then compare the results to a plan of the pyramid’s known internal voids, it might be possible to see whether there were other, unknown spaces awaiting discovery. These might be undiscovered tunnels, perhaps even secret burial chambers. In principle, they should show up in a muographic scan.

For several weeks, Alvarez and his crew lived and worked nearby, checking the machine regularly, adjusting its maze of power cables, verifying that the device was functional. What must it have been like, dwelling in the silence of a 4,500-year-old pyramid, scanning for rooms in the bulk of rock above, waiting for particles from space?

The technique worked—although Alvarez and his team found no proof of undiscovered rooms. That evidence of absence would have to wait until 2017, when the same method, using more powerful machinery and better software, did, indeed, reveal a previously undiscovered void inside the Great Pyramid of Giza. Muography as a technical means for peering inside large bodies of rock and masonry had been established.

***

My father offered to help Brandt with his vehicle that day, a generous offer that turned into a multi-hour process involving, at one point, a forty-mile roundtrip drive to the nearest autobody shop, a journey for which they invited me along in the backseat. The conversation between the two went far over my head at the time, and I remember very little of what was said. I was too young to be interested in the life stories of others, so I didn’t ask any of the questions I now have. I regret that blindness, my inability to see how deep the lives of strangers really go.

It was ten years later, when I was working on a PhD in architectural history at the University of Chicago, that my fixation on Brandt’s work truly began. By then, of course, he was dead of the pancreatic cancer that was killing him when he showed up at our door that day, and I was never able to ask him direct questions.

Wide-eyed and introspective, Brandt, I would discover, was very nearly not a physicist at all. He initially enrolled at the Technische Universität in West Berlin in 1978 to study architecture, but, well before completing his BA, found himself dreaming of other fields. Upon graduation, he applied and was accepted into the school’s physics program, and it was his thesis project there that would shape the rest of his life, ultimately bringing him to our remote town in California.

In 1983, Brandt began studying muons. He later said the idea came to him the instant he learned of Alvarez’s work in Egypt: if muons could be used to image the interiors of large structures for archaeological discovery, then, he realized, they could also be used for espionage.

The Berlin Wall stood from 1961 to its fall in 1989. In 1987, physicist Wendell Brandt began a series of muographic-imaging experiments in the basement of an abandoned church in West Berlin, spying on the East from below.

***

What Brandt did not anticipate was that the project would have an emotional charge. With each muographic exposure taking more than a month to produce, requiring him to wait for weeks at a time for something coherent to emerge in the data, the work lent itself well to contemplation. Spring became summer; summer turned to autumn. As one image became two, became three, became half a dozen, Brandt found himself thinking of friends and family he had lost to the Wall. Constructed while he was still a child, it had separated loved ones indiscriminately, with more than half of the Brandt family ending up marooned in the East.

In a project notebook I obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request, I found that Brandt had used several pages as a personal journal, reflecting on his experience developing muographic techniques in Berlin. The notes—strangely, written in English, as if he had hoped his American sponsors would someday read them—suggested a scientific curiosity gradually becoming more philosophical. Whether muons could image strategically important military features gave way to speculation about families living in apartments nearby, about the quiet lives of fellow Germans separated by the Wall—people who, he believed, he would never meet face to face. All he would know of them were these shadows and blurs, etched by cosmic particles on secret electronics in the deep.

Wendell Brandt’s experimental subterranean muon detector undergoing system corrections.

Hidden amongst hand-written numbers, pages of equations, and the occasional technical sketch were openly nostalgic notes about his own estranged relatives who, from his point of view, now lived in a kind of parallel Germany, an eerily similar reality that had branched off from his own. Where are they now? he wanted to know. Had anyone in his family ever shown up, however faintly, however briefly, in the resulting imagery? Could muons measure not just buildings, but the weight and import of an individual life?

***

Like Alvarez before him, Brandt’s proof of concept worked—but, also like Alvarez, the images revealed no unusual or exciting anomalies. Their quality was debatable, the resolution too low. Brandt’s sponsors wanted something as crisp as a medical X-ray, but what they got resembled a photocopy of a floorplan drawn from memory. Was this a problem of the technology itself, Brandt wondered—an inherent limit to muography—or was the problem one of exposure time? If he could sit beneath the streets of Berlin for years, could he image individual rooms? If he had decades, could he detect the presence of a single stranger?

Nevertheless, Brandt had convinced his American benefactors that muon imaging worked on an urban scale. Toward the end of 1988, a new, smaller grant was approved, his lab’s staffing was cut, and Brandt soon found himself truly alone, continuing the project for another cycle.

When the Wall unexpectedly fell in November 1989, Brandt was in a hotel in Washington DC, attending meetings with his federal funders. After the news broke, his hosts allowed him to fly home early, to see estranged friends and family on the streets of a reunited Berlin. It was made clear less than two weeks later that the entirety of Project Horus was to be dismantled, and Brandt’s equipment and data, even his laboratory notebooks, given to the US government for future reference and study. Current events had brought the experiment’s strategic relevance to an end, its cost no longer justifiable.

Although the resulting images were quite low-resolution, Brandt successfully demonstrated that muography could be used for international espionage.

In terms of science, however, and by the project’s own goals, Horus was a success. The United States had surreptitiously imaged an estimated forty buildings in East Berlin. While the resolution was so low that it was, at times, difficult to differentiate one structure from another, subterranean espionage using cosmic particles across an international border in a conflict zone had proven not just possible, but, by military standards, cheap.

Whether out of dark humor or bureaucratic laziness, someone at the Department of Defense scheduled the lease on the church near Heinrich Heine Strasse to expire Christmas Day. Brandt spent several hours alone in the project crypt that morning, but left no notes about what he was thinking.

***

Brandt spent the 1990s teaching physics in a reborn Germany, working on what appeared at the time to be an unsurpassably quixotic project in advanced muography. Tapping into his earlier years studying architecture and working with technicians from Berlin’s celebrated film industry, Brandt designed and constructed an experimental building with no other purpose than to be imaged from below with muons.

Featuring sixty-four precisely measured rooms and a simulated elevator shaft, and built with materials of known weight and density, the Muon Calibration House, as he called it, was assembled on a former warehouse site in the rapidly gentrifying neighborhood of Prenzlauer Berg. Muon detectors of different sizes and strength were installed in lead-lined basement rooms at specific metric depths. The rooms themselves were arranged in special grids to create positive or negative feedback with spaces on other floors, and heavy rails were installed, across which enormous, wheeled carts could be shifted, pulling obstacles room to room.

There, over the course of nine years, Brandt and visiting researchers produced thousands of muographs to probe the sensitivity and limits of particular instruments. Dense materials mounted on carts—their weight so extreme they would have caused a normal building to collapse—were moved from point to point, sometimes continuously, at speeds as slow as one centimeter per day, to see how they registered in the scans. One detector was left running for the entirety of the year 1997 to record literally every movement inside the structure. Objects of different densities were placed one above the other to explore shadowing effects and interference. Brandt wanted to know if it was possible to build muographic countermeasures—obstacles, decoys, camouflage, false positives—and if it was thus possible to hide something from muographic view. How do you prevent something from casting a shadow into the Earth?

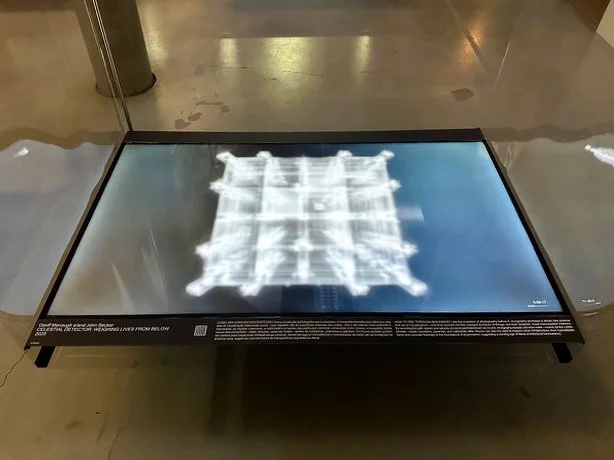

To human eyes, Brandt’s calibration house looked like a theatrical set; to the muon detectors, it looked like a mesh of gates, pores, and openings through which celestial particles endlessly roared. What emerged was a body of images and data still considered by many physicists to be the gold standard for muographic calibration.

From the detectors’ point of view, he realized, cities were just clouds of walls and foundations, with people’s lives passing overhead like storm systems. Elevator shafts recorded in the data like tornadoes, great throats of space coiling upward as room-size objects heaved up and down. He imagined a thousand-year muon scan, a thousand-year precession of streets, rooms, and cities showing up in the data. Brandt seemed to believe that the surface of the Earth was, in a sense, a slow extension of the sky: translucent, weightless, adrift. For an observatory ten meters underground, “we are all astronomy,” he wrote—our daily lives, our houses and roads, all celestial events—as much a part of the sky as the weather or the stars.

***

The land on which the calibration house was constructed was eventually sold, the building itself demolished to make way for a new housing complex. It is likely the most precisely measured work of architecture of the twentieth century: a building scanned down to the last millimeter, recorded and re-recorded over years at a time.

No images produced there have been published outside of technical journals—and, even then, only around one hundred have seen the light of day. Nearing the end of my PhD research, I received a series of PDFs from one of Brandt’s former colleagues, containing nearly five thousand muographic exposures. They ranged from the comically basic—a clearly-defined grid of rooms with a single, high-mass object positioned in the mathematical center of the first floor—to situations so spatially complex they resembled a puzzle, a fiendish maze to be solved only through advanced software processing.

In these early images from the Muon Calibration House, Brandt and his colleagues were able to detect and visualize individual rooms and masses.

Once again, Brandt’s relationship to the experiment was not what I anticipated. In emails he sent to former colleagues, which I was able to read after many months of pestering, Brandt wrote that he would spend time inside the building alone among the detectors—“my detectors,” he called them—in what sounded, to my ears, like a meditative state. He would often go specifically on Sundays, he wrote, not for religious reasons but to avoid running into anyone. He would sometimes lie on the floor, muons falling down around him like rain, and contemplate the rooms above, the carefully positioned objects, the precisely known dimensions of every space—and the total lack of human beings.

It made him think, once again, about the challenge of capturing the flash and detail of an individual life. For a man seemingly obsessed with spending time by himself, he was equally obsessed with the lives of others. For muons, he knew, matter was easily perforated; but, for Brandt, strangers seemed impenetrable.

***

In the autumn of 2003, Brandt arrived in Los Alamos, New Mexico, part of a sprawling team of physicists at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. The effort that brought him there was intended to explore whether muons could be used to map immensely large-scale geological structures, such as calderas and volcanoes.

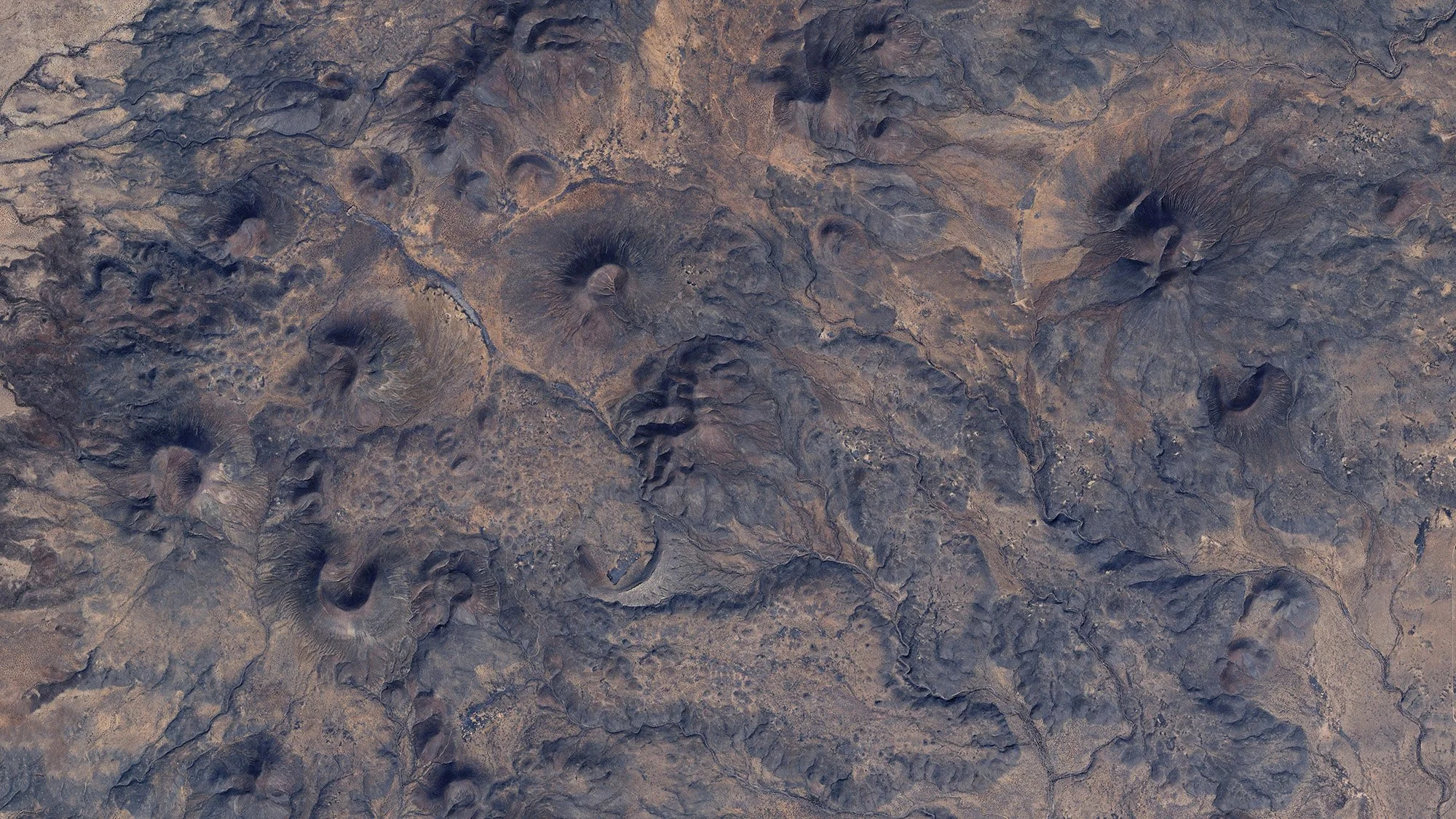

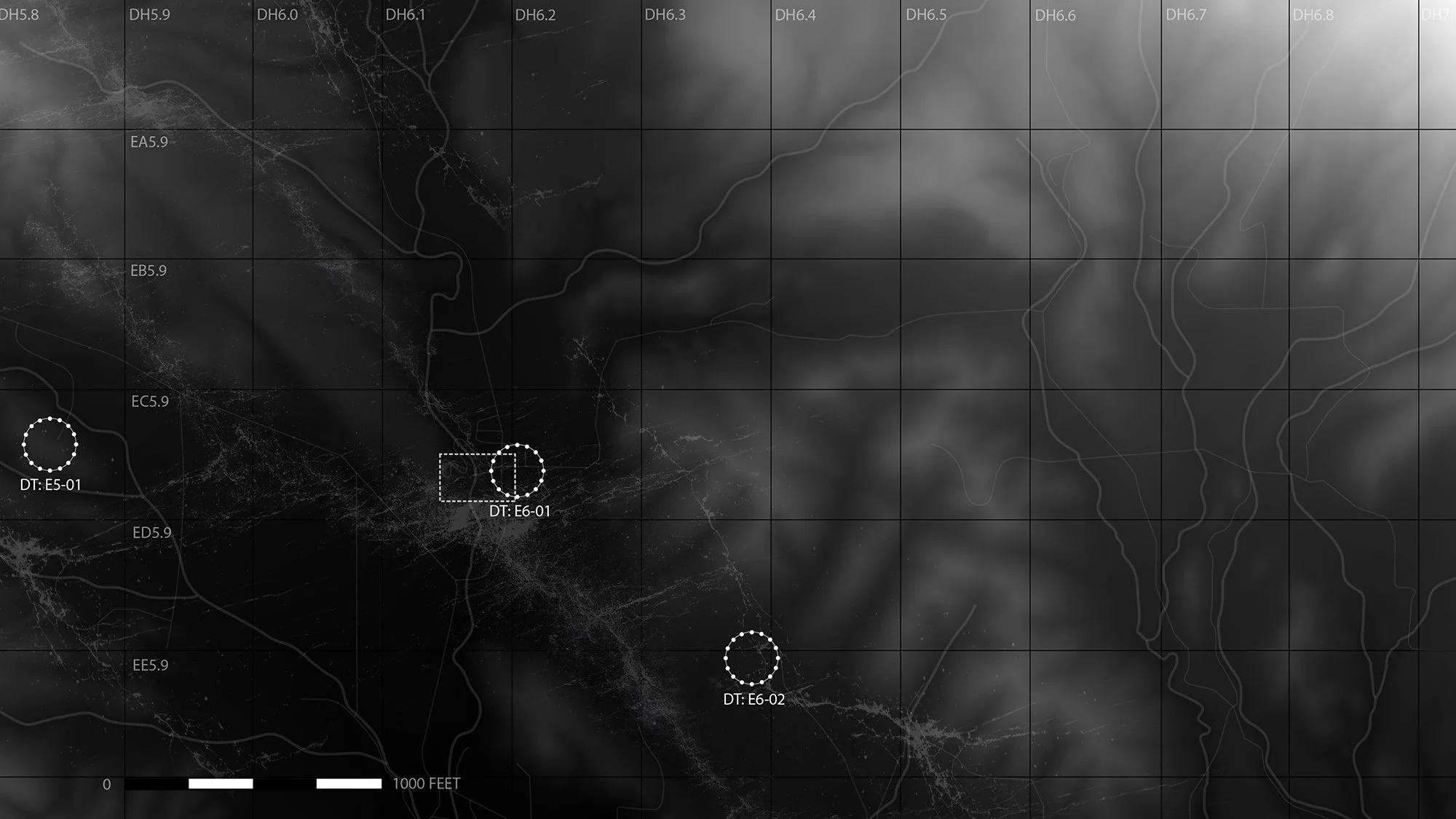

The Potrillo volcanic field in southern New Mexico covers an area more than four hundred square miles in size. In 2003, Brandt began imaging the region from below as part of an effort funded by the National Science Foundation. Image: compiled and modified by WROT, based on Google Maps (Airbus, CNES/Airbus, Landsat/Copernicus, Maxar Technologies).

Although the method would not truly succeed until 2007—when a Japanese team led by physicist Hiroyuki Tanaka imaged the interior structure of a stratovolcano called Mt. Asama—the Los Alamos group made headway. Brandt, in particular, had a conceptual breakthrough, driven perhaps by his special request to work alone, at a more challenging site. While the participating American scientists stayed together in collaboration at the Valles Caldera, an extinct supervolcano just behind the National Laboratory, Brandt spent most of his time at the distant Potrillo volcanic field, nearly on the US-Mexico border.

Constrained by limited funding, the shafts and tunnels housing Brandt’s muon-detector arrays were accessible through rudimentary Quonset-style huts. Here, as in Berlin, Brandt spent most of his time alone.

There, he supervised a network of muon detectors installed beneath an area of dead volcanoes more than four hundred square miles in size. Magma chambers, lava tubes, interconnected caves and tunnels: Brandt’s images revealed tantalizing glimpses of each. But, while there, he became fixated on other geological problems entirely, not of volcanic features frozen in place, but of moving events, of phenomena muography should not have been able to see.

Brandt’s muon arrays suggested that large-scale geological processes could, given enough time, be imaged using cosmic particles, inspiring an idea that later brought him to California.

This was the question that would bring him to my small town in California, a town remarkable only for being located directly above the San Andreas Fault.

***

Brandt first arrived here in the spring of 2008, spearheading a project to image an active fault line with muography. In both Berlin and New Mexico, he had seen that subtle spatial events could be recorded, using multiple detectors. The prospect of capturing a large-scale dynamic process—for example, seeing a fault in the process of cracking open, unleashing an earthquake—animated his next phase of research.

Our town was infamous amongst geologists, who arrive on field trips throughout the year to take photographs of road signs pointing out the path of the San Andreas, which runs beneath our homes and streets like an underground river. In the 1970s, the US Geological Survey even determined that the region was so overdue for a large quake, they outfitted our town with as many seismic sensors as grants could afford. If the big one finally hit, they believed, they would be watching, ready—and, able to go back through years of data, they might find earlier, missed warnings of what was to come. They are still waiting; the earthquake has yet to happen.

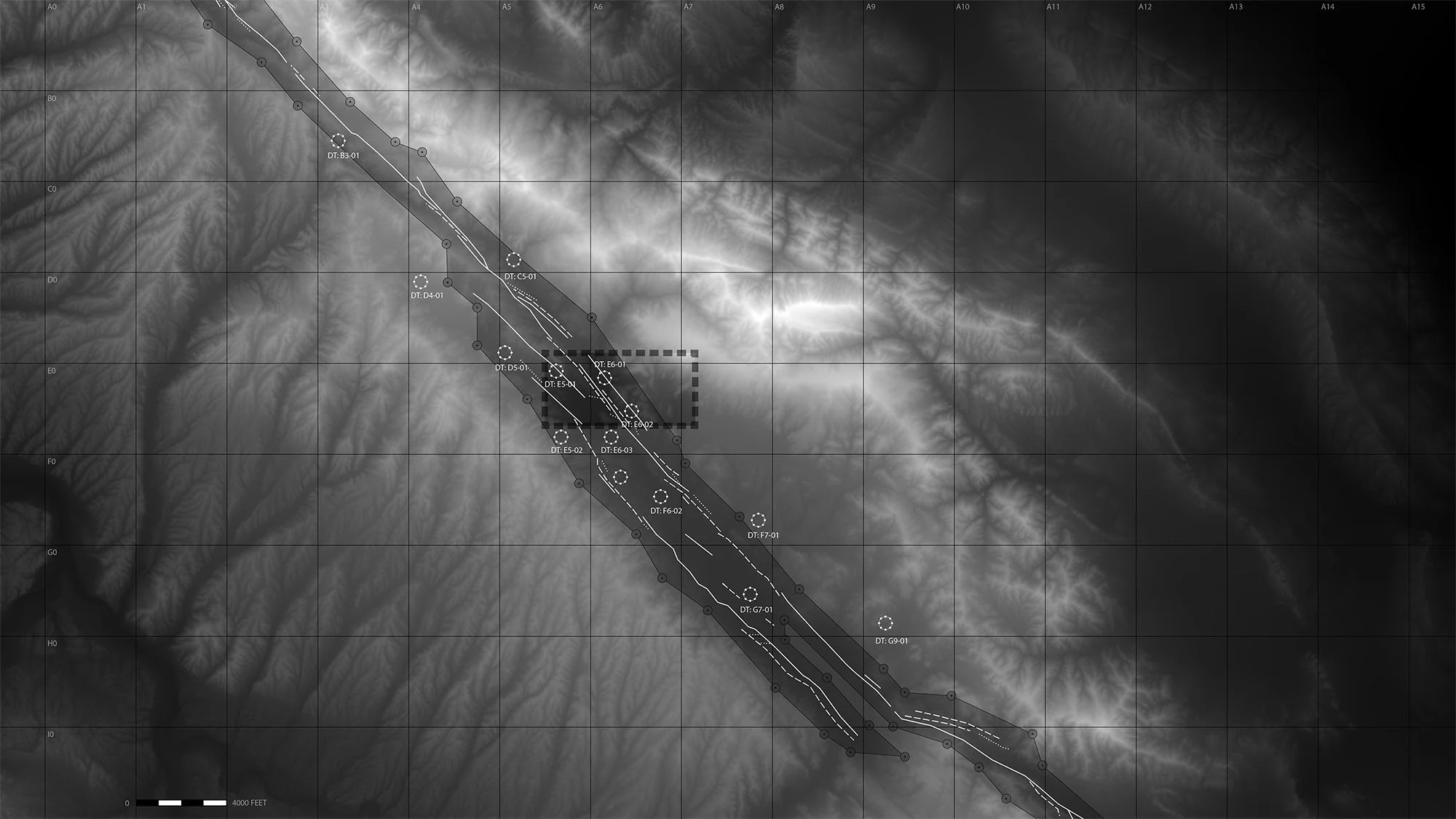

As was his habit, however, Brandt had his own ideas. The lab he constructed in our town grew over the years in both size and complexity. Circular muon-capture arrays, featuring dozens of linked detectors, were installed in multi-level underground rooms, shielded by lead walls designed to resist interference. Corridors wove across the fault and back again. Unbeknownst to us, they infiltrated deep under our town, beneath our streets, schools, and houses.

In 2008, Brandt began constructing and overseeing an ambitious experimental muography program that sought to image tiny movements along the San Andreas Fault. His detectors were embedded in the fault itself, but also extended under the streets and homes of a nearby town, where I grew up.

My dad said he only ever saw the lab’s electrical room, a utilitarian cinderblock structure the size of a domestic house on the northern edge of town. But, during a visit to a National Science Foundation archive during my final thesis research, I was able to piece together the layout of Brandt’s labyrinth. If the Muon Calibration House in Berlin had seemed ambitious for its time, this facility put it to shame: it was a veritable octopus of rooms, hallways, and high-tech electronics. From a detection corridor running roughly the length of four football fields, ten boreholes dropped a further six hundred feet, each housing an experimental detector, placing a chandelier of instrumentation directly in the path of the fault.

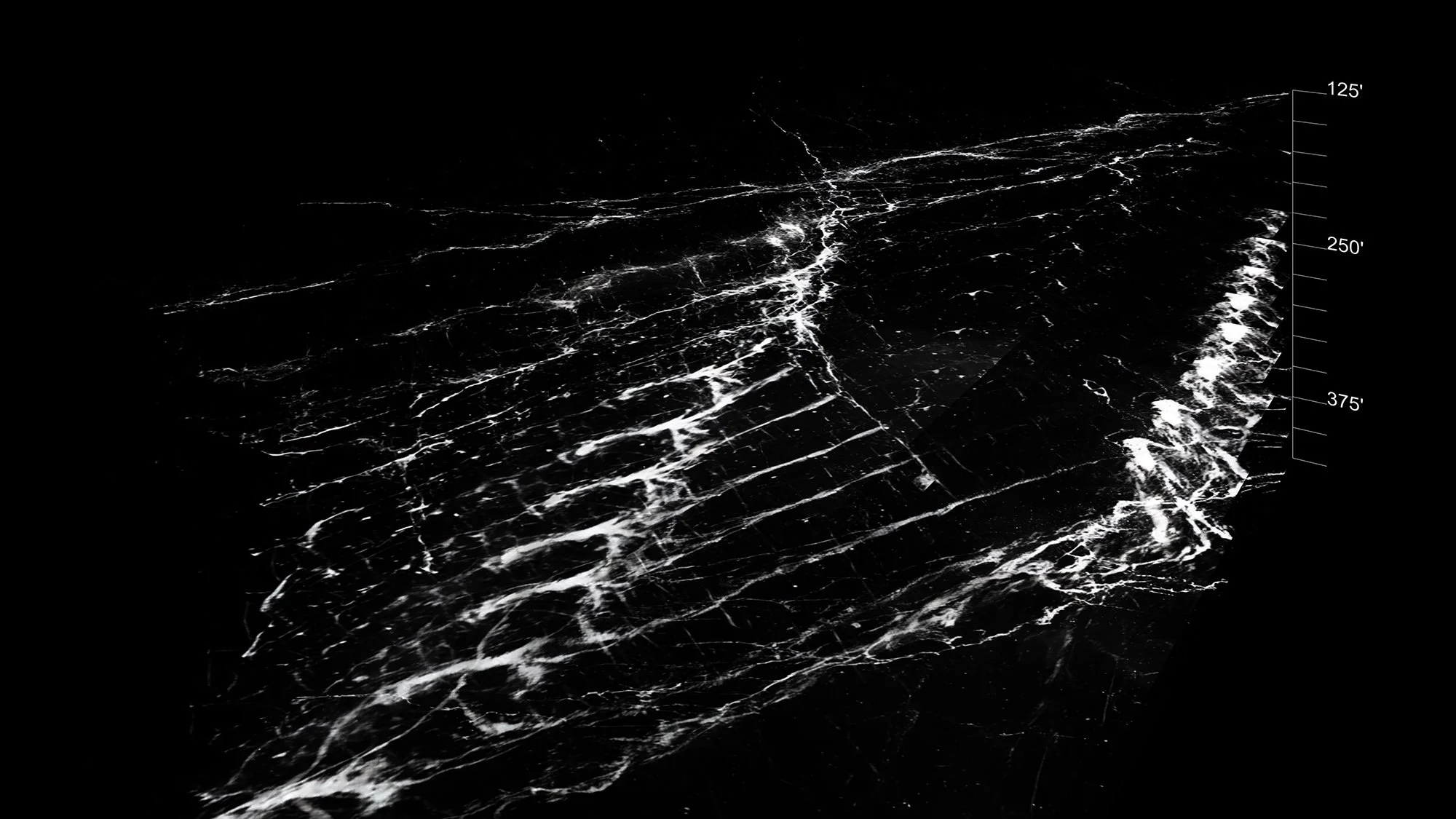

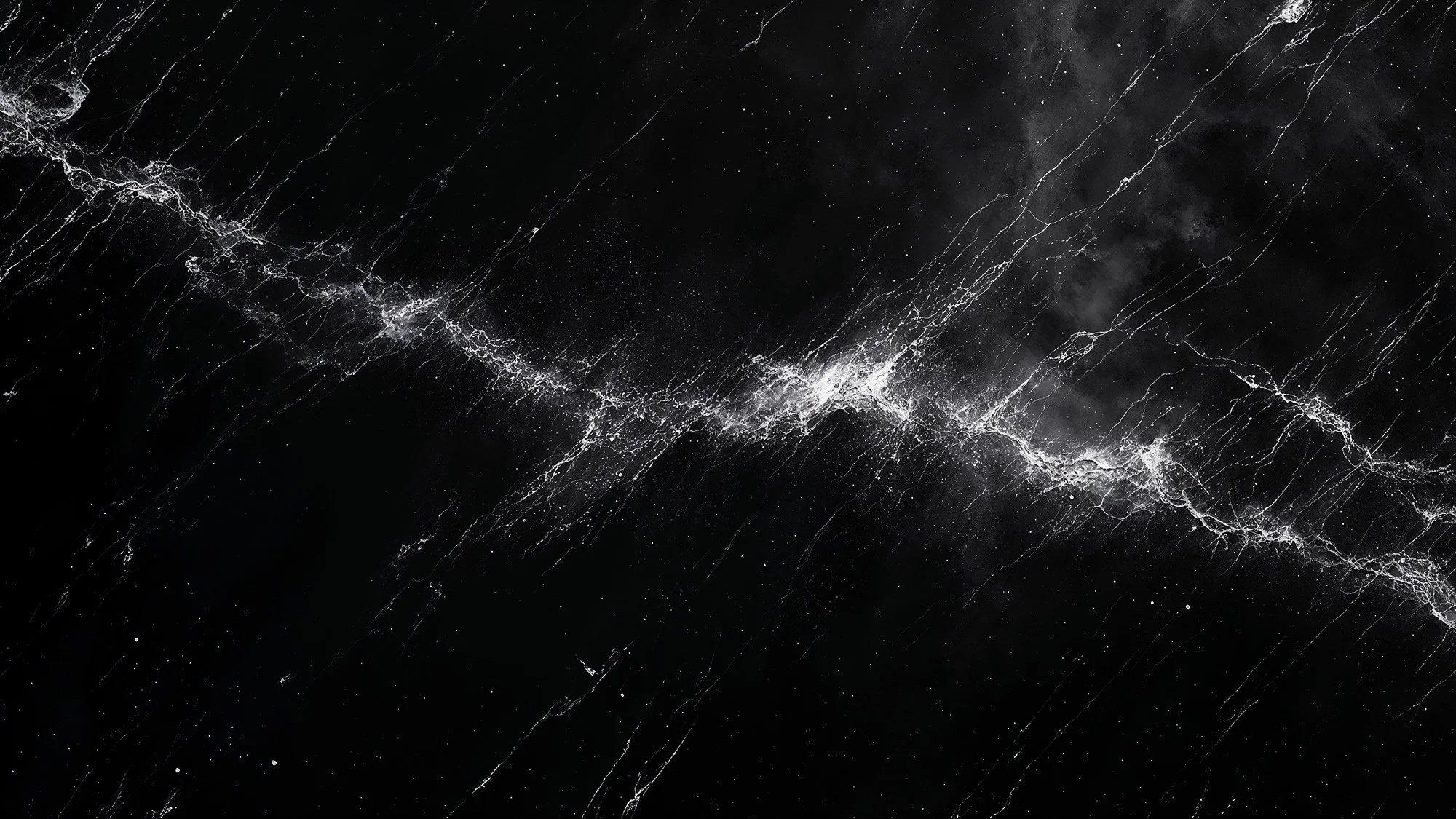

The resulting muographic images and three-dimensional models of the San Andreas Fault resembled auroras inside the Earth.

Recording muons over the course of more than fifteen years, Brandt sought to capture even the smallest movement of one tectonic plate against the other—a millimeter here, a millimeter there; the tiniest growing gaps or strains. The images he produced were unlike any I had ever seen before: instead of the clear, geometric lines of an architectural structure, the fault resembled the Northern Lights, an aurora sizzling underground, a windblown form that drifted like a curtain. It was eerily beautiful.

For Brandt, muon detectors—endlessly staring up at the Earth’s surface from below—revealed that “we are all astronomy,” something indicated visually by this image of this muograph of the San Andreas Fault.

There was something else in the images. With dozens of detectors pointing upward, not only at muons, but at our town, Brandt had seen the emergent shapes of our homes and buildings right away, squares and rectangles faintly visible above the jagged slash of the fault.

Brandt, over fifteen years, had time on his hands. Specific houses, he found, could be imaged down to their every room, down even to the furniture in those rooms—down even, Brandt saw to his astonishment, to tiny blurs that appeared to be human beings. A man in a reclining chair, watching TV every night for decades, in the exact same place, eventually leaves a shadow. My family’s dining room furniture cast a shadow. My parents’ lives were marked in muons.

In Brandt’s multiple-year exposures of our town taken from below, individual rooms, even specific pieces of furniture, became visible.

“We are all astronomy,” Brandt had once written. He pushed this insight further with an eccentric after-project report that, in characteristic fashion, blended the scientific with the personal. “What do we weigh?” he wrote. “What do we truly weigh?”

When he came to our front door that day, an old man dying of a cancer he had been too late to detect, its blurred but fatal shadow something that should have been spotted on X-rays years before, Brandt had wanted to see one final time a world he had been watching from below.

***

We all cast shadows into the Earth. We leave traces in the deep. Things fall from the heavens and pass through us, always. We affect and change those subtle messengers, diverting their path and velocity: after us, because of us, through us, the world is given new meaning by what they reveal. But, when we ourselves pass on—residents of a planet we will never know in full, dwellers of cities and homes we’ll never measure in their entirety—it is too late to see how we’ve changed what we have passed through.

E-FLUX PUBLICATION

Special Thanks to John Palmesino and Ann-Sofi Rönnskog (Territorial Agency), curators of the 7th Lisbon Architecture Triennale.

Notes

For a useful, albeit technical introduction to muons and muography, see Lorenzo Bonechia, Raffaello D’Alessandro, and Andrea Giammanco, “Atmospheric muons as an imaging tool,” Reviews in Physics 5 (2020). For an interview with Raffaello D’Alessandro on his research imaging large works of architecture with muography, see Geoff Manaugh, “A tiny particle can travel through concrete. It could save many lives,” Financial Times Magazine (September 7, 2022).

Eric George, “Cosmic Rays Measure Overburden of Tunnel,” Commonwealth Engineer (July 1, 1955).

Luis W. Alvarez, Jared A. Anderson, F. El Bedwei et al., “Search for Hidden Chambers in the Pyramids: The Structure of the Second Pyramid of Giza is Determined by Cosmic-ray Absorption,” Science 167, no. 3919 (February 6, 1970): 832–39.

Kunihiro Morishima et al., “Discovery of a big void in Khufu’s Pyramid by observation of cosmic-ray muons,” Nature 552 (2017).

Hiroyuki K. M. Tanaka and Izumi Yokoyama, “High resolution imaging in the inhomogeneous crust with cosmic-ray muon radiography: The density structure below the volcanic crater floor of Mt. Asama, Japan,” Proceedings of the Japan Academy, Series B (2008). See also Tanaka et al., “Development of an emulsion imaging system for cosmic-ray muon radiography to explore the internal structure of a volcano, Mt. Asama,” Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A (June 1, 2007) and Tanaka, “Japanese volcanoes visualized with muography,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A (2019).

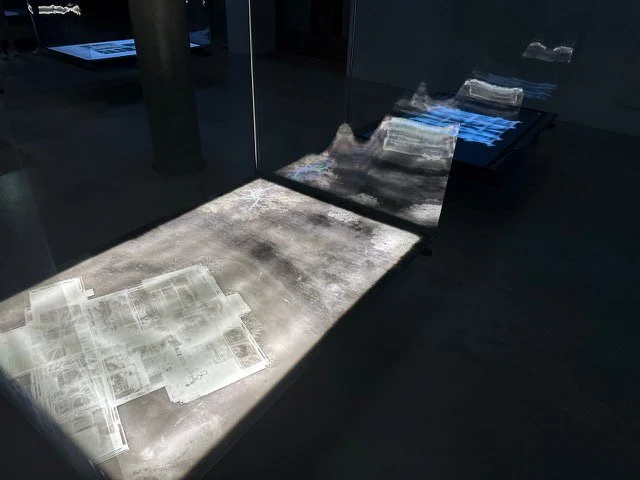

HOW HEAVY IS A CITY?

7th Lisbon Architecture Triennale

Photos of the Lisbon Architecture Triennale (Photography by Sara Constanca)

Photos of Celestial Detector: Weighing Lives from Below displayed in the exhibition. (Photography by Territory Agency)